What follows is a tale that, for business people, reads like a Shakespearean tragedy – or a Stephen King horror novel. It starts with the recent history-setting success of Avengers: Endgame and the notion that an idea has value – and if you don’t see it or won’t realize it, someone else will.

The year is 1998. As explained in this Wall Street Journal piece, Sony Pictures wanted to buy the rights to produce Spider-Man movies. Marvel Entertainment, who owned the rights, needed cash because they had just came out of bankruptcy. So, Marvel essentially told Sony that not only could it have the rights to Spider-Man, it could have the rights to almost every Marvel character for the low-low sum of $25 million.

These Marvel characters? They included Iron Man, Thor, Black Panther, and others. You may recognize those names, unless you’ve sworn off entertainment altogether for the past decade.

Sony said “No thanks, we just want Spider-Man,” and only paid $10 million in cash.

Eleven years and 22 movies later, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) has grossed a staggering $19.9 billion (as of 4/30/2019) – and they’re not done making movies, with plenty more on the way.

Sony’s decision was an epically bad one, of course, but only in hindsight. There’s no guarantee that even if they had bought the rights that they would’ve had the same success. Besides, there’s no way they could’ve predicted just how valuable the franchise would turn out to be. After all, at the time, the cinematic prospects for many of the characters that were for sale were low, to say the least. Part of that is due to a decade-long slide in quality and popularity for Marvel in the 1990s that eventually lead to its bankruptcy.

Measuring value for an idea is impossible. You just can’t predict what movies – or books, or songs, or works of art, or ideas in general – will be successful…right?

Finding the Next Hit: Measuring the Potential Value of an Idea

One pervasive belief is that you can’t measure or quantify an intangible thing like an idea, like a movie. People believe that you can only quantify tangible things, and even then, it’s difficult to forecast what will happen.

Ideas, though, can be measured just like anything else. Can you put an exact number on an intangible concept, like whether or not a movie will be a success? No – but that’s not what measurement and quantification are, really.

At its most basic, measurement is just reducing the amount of uncertainty you have about something. You don’t have to put an exact number on a concept to be more certain about it. For example, Sony Pictures wasn’t certain how much a Spider-Man movie would make, but it was confident that the rights were worth more than $10 million.

One of the most successful superhero movies in the 1990’s – Batman Forever, starring Val Kilmer, Jim Carrey, and Tommy Lee Jones – raked in $336.5 million on a then-massive budget of $100 million.

If we’re Sony and we think Spider-Man is roughly as popular as Batman, we can reasonably guess that a Spider-Man movie could do almost as well. (Even a universally-panned superhero movie, Batman & Robin, grossed $238.2 million on a budget of $125 million.) We can do a quick-and-dirty proxy of popularity by comparing the total number of copies sold for each franchise.

Unfortunately there’s a huge gap in data for most comics between 1987 and the 2000’s. No matter. We can use the last year prior to 1998 in which there was industry data for both characters. Roughly 150,000 copies of Batman comics were sold in 1987, versus roughly 170,000 copies of Spider-Man.

Conclusion: it’s fair to say that Spider-Man, in 1998, was probably as popular as Batman was before Batman’s first release, the simply-named Batman in 1989 with Michael Keaton and a delightfully-twisted Jack Nicholson. Thus, Sony was making a good bet when it bought the rights to Spider-Man in 1998.

Uncertainty, then, can be reduced. The more you reduce uncertainty through measurement, the better the decision will be, all other things considered equal. You don’t need an exact number to make a decision; you just have to get close enough.

So how can we take back-of-the-envelope math to the next level and further reduce uncertainty about ideas?

Creating a Probabilistic Model for Intangible Ideas

Back-of-the-envelope is well and good if you want to take a crack at narrowing down your initial range of uncertainty. But if you want to further reduce uncertainty and increase the probability of making a good call, you’ll have to start calculating probability.

Normally, organizations like movie studios (and just about everyone else) turn to subject matter experts to assess the chances of something happening, or to evaluate the quality or value of something. These people often have years to decades of experience and have developed a habit of relying on their gut instinct when making decisions. Movie executives are no different.

Unfortunately, organizations often assume that expert judgment is the only real solution, or, if they concede the need for quantitative analysis, they often rely too much on the subjective element and not enough on the objective. This is due to a whole list of reasons people have for dismissing stats, math, analytics, and the like.

Doug Hubbard ran into this problem years ago when he tapped to do exactly what the Sony executives should’ve done in 1998: create a statistical model that will predict the movie projects most likely to succeed at the box office. He tells the story from his book How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of “Intangibles” in Business:

The people who are paid to review movie projects are typically ex-producers, and they have a hard time imagining how an equation could outperform their judgment. In one particular conversation, I remember a script reviewer talking about the need for his “holistic” analysis of the entire movie project based on his creative judgment and years of experience. In his words, the work was “too complex for a mathematical model.”

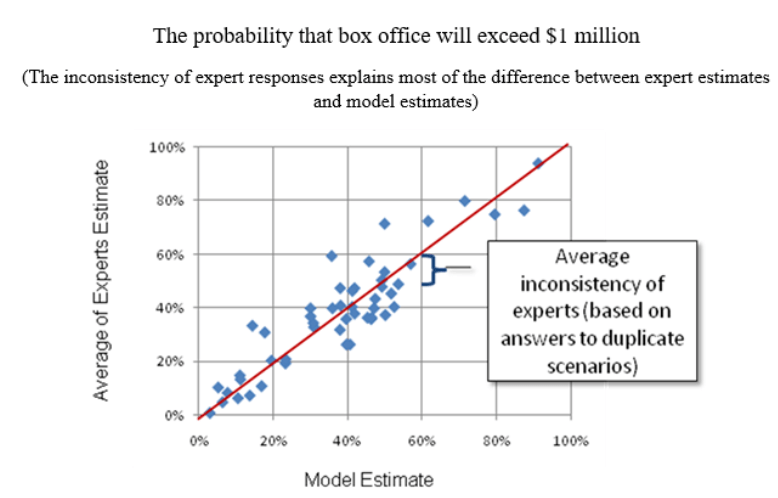

Of course, Doug wasn’t going to leave it at that. He examined the past predictions about box office success for given projects that experts had made, along with how much these projects actually grossed, and he found no correlation between the two. In fact, projections overestimated the performance of a movie at the box office nearly 80% of the time – and underestimated performance only 20% of the time.

Figure 1 compares expert assessment and a model of expert estimates, using data points from small-budget indie films:

Figure 1: Comparison Between Expert Estimates and the Model Estimate

Figure 1: Comparison Between Expert Estimates and the Model Estimate

As Doug says, “If I had developed a random number generator that produced the same distribution of numbers as historical box office results, I could have predicted outcomes as well as the experts.”

He did, however, gain a few crucial insights from historical data. One was that there was a correlation between the distributor’s marketing budget for a movie and how well the movie performed at the box office. This led him to the final conclusion of his story:

Using a few more variables, we created a model that had a…correlation with actual box office results. This was a huge improvement over the previous track record of the experts.

Was the model a crystal ball that made perfect, or even amazingly-accurate predictions? Of course not. But – and this is the entire point – the model reduced uncertainty in a way that the studio’s current methods could not. The studio in question increased its chances of hitting paydirt with a given project – which, given just how much of a gamble making a movie can be, is immensely valuable.

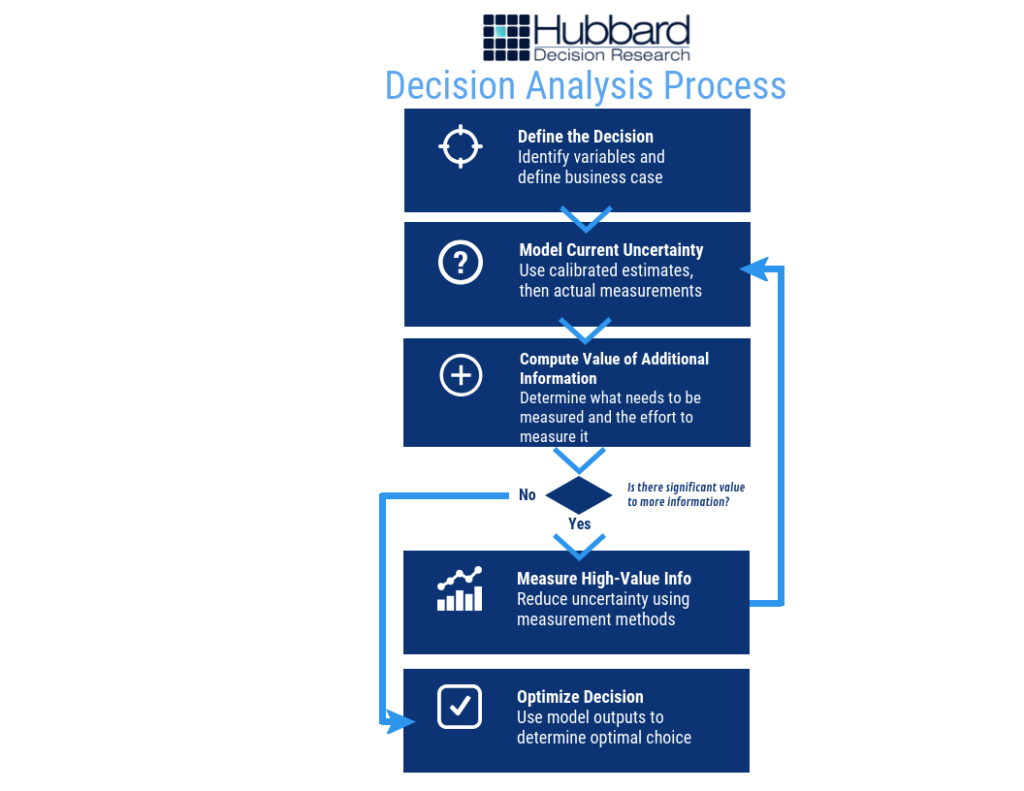

The process for creating a model is less complicated than you might think. If you understand the basic process, as shown below in Figure 2, you have a framework to measure anything:

Figure 2: Decision Analysis Process

Figure 2: Decision Analysis Process

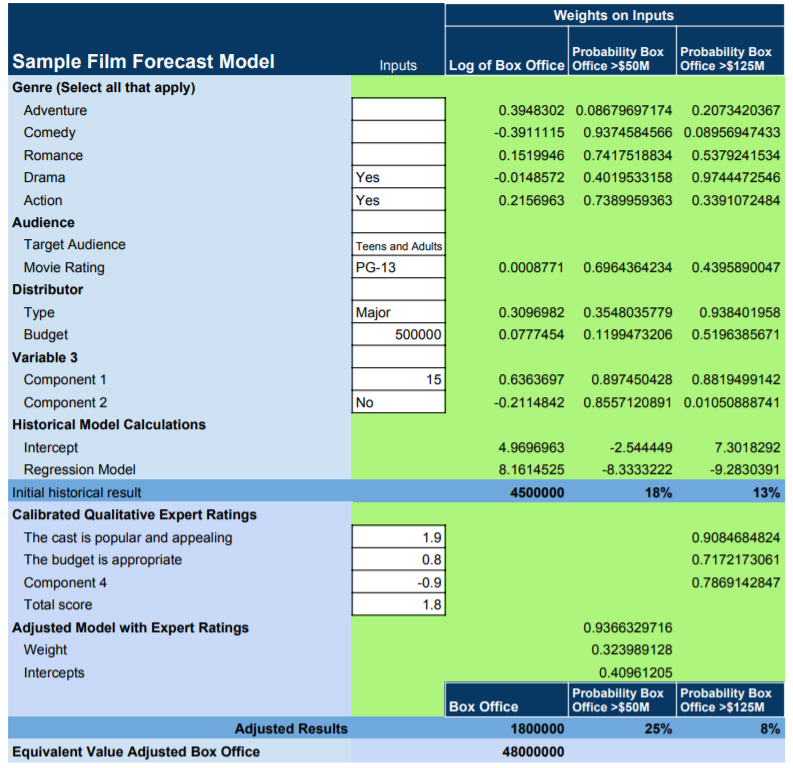

At its core, a model takes variables – anything from distributor budget for movies to, say, technology adoption rate for business projects – and uses calibrated estimates, historical data, and a range of other factors to put values on them. Then, the model applies a variety of statistical methods that have been shown by research and experience to be valid and creates an output that can look like this in Figure 3 (the numbers are just an example) :

Figure 3: Sample Film Forecast Model

Figure 3: Sample Film Forecast Model

What’s the Next Big Hit?

The next big hit – whether it’s a movie, an advertising campaign, a political campaign, or a ground-breaking innovation in business – can be modeled beyond mere guesswork or even expert assessment. The trick – and really, the hard part – is figuring out how to measure the critical intangibles inherent to these abstract concepts. The problem today is that most quantitative models skip them altogether.

But intangibles are important. How much your average fan loves a character, and will spend hard-earned money to go to a movie theatre to see an upcoming film about, say, a biochemist-turned-vampire named Morbius, will ultimately help to determine success. Expressed in that desire – in any desire – are any number of innate human motivations and components of personality that can be measured.

(By the way, the aforementioned Morbius movie is being made by Sony as a part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Better late than never, although you don’t need a model to predict Morbius won’t gross as much as Avengers: Endgame, despite how cool the character may be.

In this world, precious few things are certain. But with a little math and a little ingenuity, you can measure anything – and if you can measure it, you can model and forecast it and get a much better idea of what will be the next great idea – and the next big hit.